One of the points we are going to stress in our GRIP course “Not Just Farmers,” is to keep looking. Don’t stop just because one thing didn’t turn up any records for you. There are always more databases, digitized collections, online books, and so much more to find.

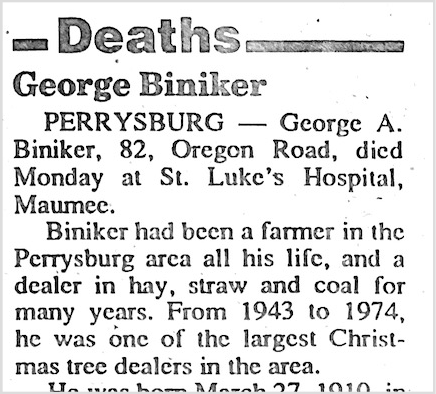

I have been researching my third great-grandfather for years. Samuel Cook Dimick and his son Marshall Chester worked a farm east of Bowling Green, Ohio, in Wood County. A few years ago I dug deeper into his life to develop his timeline for my lecture on the subject. I found so many new records about him during that research that I figured I had probably reached near the most of what I could find.

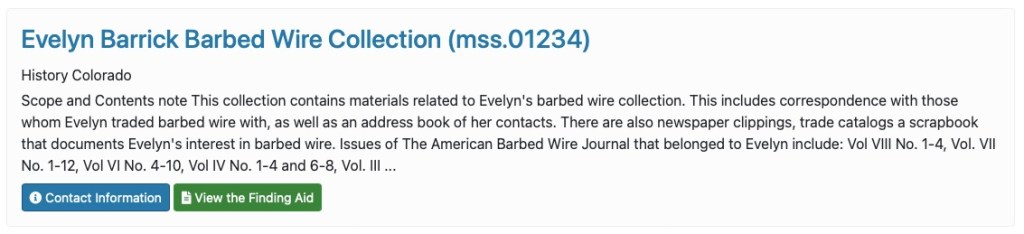

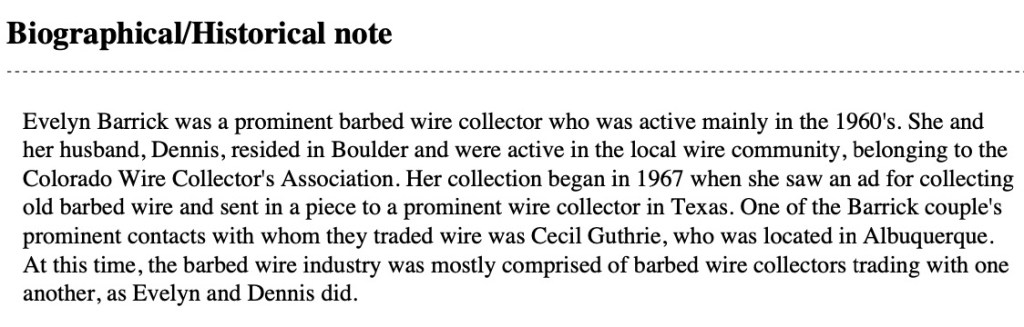

For this course, I am using him as one of my example farmers because I had already gathered so much information on him. However, while preparing for these new topics on farming, I have found so much more! Tidbits on his farm, crops, social activities in farming clubs, his involvement in the Prohibition movement, experiments and data collection he took part in for scientific studies, etc. During this work, I found new and exciting digitized collections I could access from home. I also found many finding aids and collections that I need to access in person (either myself or by hiring a researcher to go on my behalf).

My point in sharing this is to encourage you to keep looking, digging, clicking, and reading. Below are a few new things I learned about Samuel Cook Dimick.

He took part in a data collection study to improve the sugar beet industry. He was listed in an 1898 report to the Federal Government which indicates that he grew a variant called “Vilmorin’s Improved” sugar beets and the average weight and amount of sugar in the beet was collected. It also recorded that the season was favorable that year.

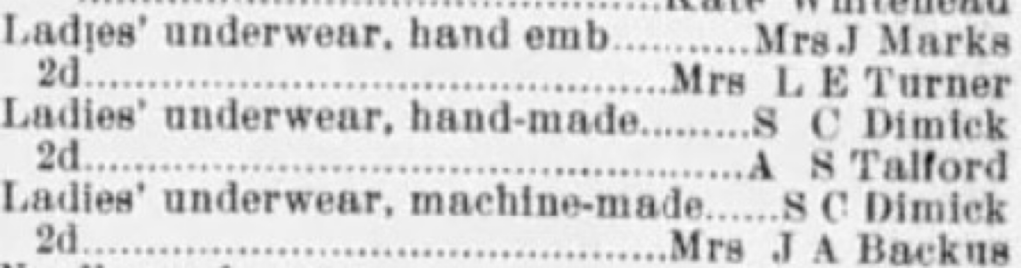

He entered some items in the Wood County Fair in the “Plain Needle Work” category:

I had no idea.

The things you learn when you keep on clicking!