I know at the end of the last post I said I would next be talking about the Ancestry catalog. But as I started that, I felt like I needed to give a little background on why I’m even writing this series. I’ve probably talked about this before on this blog, but it is so important, that I’m going to say it again. Good research begins with a good research question. If you don’t know what you are looking for, how are you going to know when you find it?

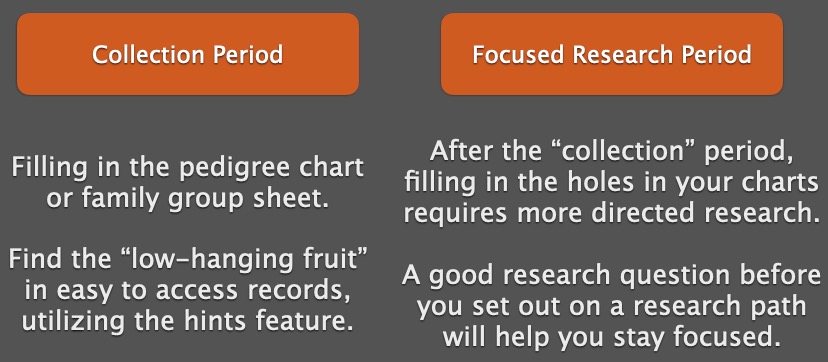

I talked previously in this series about the two phases I’ve seen and experienced throughout my genealogical lifespan, collecting and then focused research.

Having a good research question guides your research in the second phase. It helps tell you where to look for answers.

There’s a Goldilocks effect when it comes to research questions. They can be too broad, too narrow, or just right. And we aim for the “just right” question. The question needs to identify a unique person in time and place, and it needs to be answerable. For example:

Who were the parents of Thomas Carroll Mitchell who died in Montgomery County, Missouri on 29 April 1914?

This question identifies a unique person by giving a full name and death date and location. It says “I’m talking about this specific Thomas Mitchell, not the man of the same name who lived two counties over and died a year later.”

A question too broad will not give those details: Who was Thomas Mitchell? Who were Thomas Mitchell’s parents? When was Thomas Mitchell born? All these only provide a name, and not a full name (use it if you have it), and not location or dates. There are far too many Thomas Mitchells in the world for these to be useful questions. They do not give enough information to even know where to start.

A question too specific might be: What was Thomas Carroll Mitchell’s exact date of birth? Believe it or not, some people did not know their exact birth dates, or records may not have been left that provide that information. A better question might ask for “when was he born” which can be answered with a date range or a year only.

The “just right” question will give enough information to guide our research. Let’s look at the example above. From that question, we know where and when Thomas died. Likely we have a document (death certificate or burial records) that provided that information. Now, we can work backwards to try to identify his parents. We know he died in 1914, so one step in our research plan might be to find him in all of the censuses starting with 1910 in Montgomery County, Missouri, provided he didn’t recently move there.

Based on what you find in the censuses, you then decide where to go from there. Part of that is what I call “pre-research.” How do you know where to go to find the records you want to look at? Guess what. It’s the catalog.