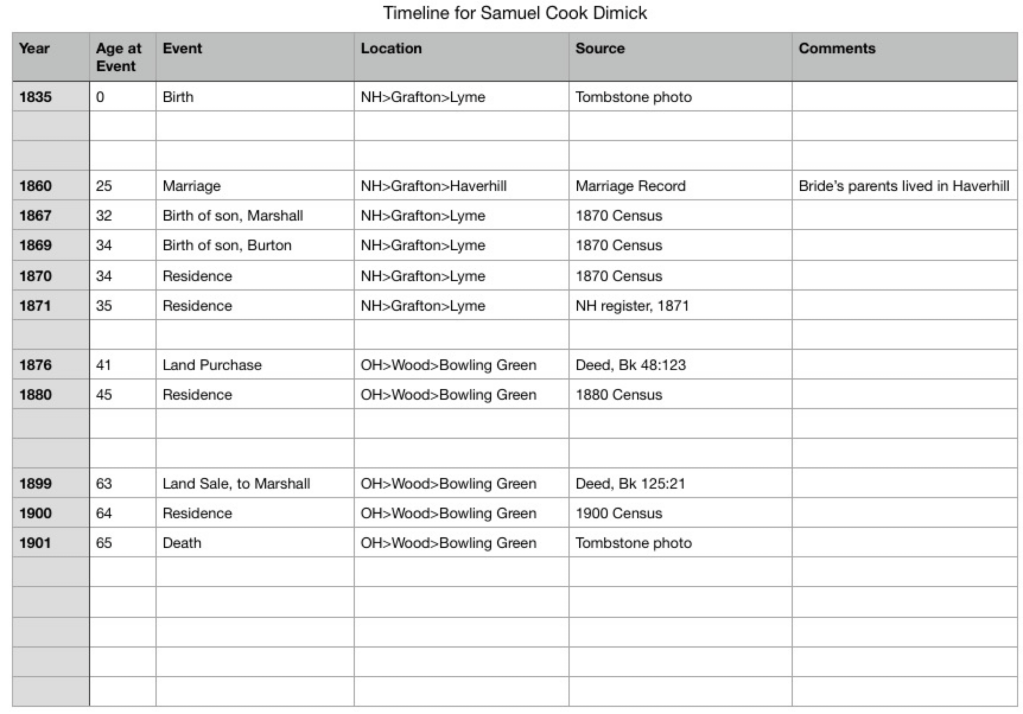

I mentioned my timeline for my ancestor Samuel Cook Dimick a few blog posts ago. Let’s take a look at his story. When I was first researching him, one of my main questions was “why.” Why did he take his family away from New Hampshire (where it is beautiful, I’ve visited) to Wood County, Ohio? Wood County is about as flat as flat can be (well, with the exception of large parts of Kansas and eastern Colorado, but I digress). Why was I from Ohio and not New Hampshire?

I have a fantastic county history entry for Samuel in the Wood County History. It has so many details about him and his family. I started corroborating that biographical sketch with documentary research. I set out to prove (or disprove) each point. (I’m still working on a few points that I need to do onsite research for, but it is mostly finished – and all points proven so far.) I started by making a timeline of the known information I had for him and then started adding those points from the county history as I proved them.

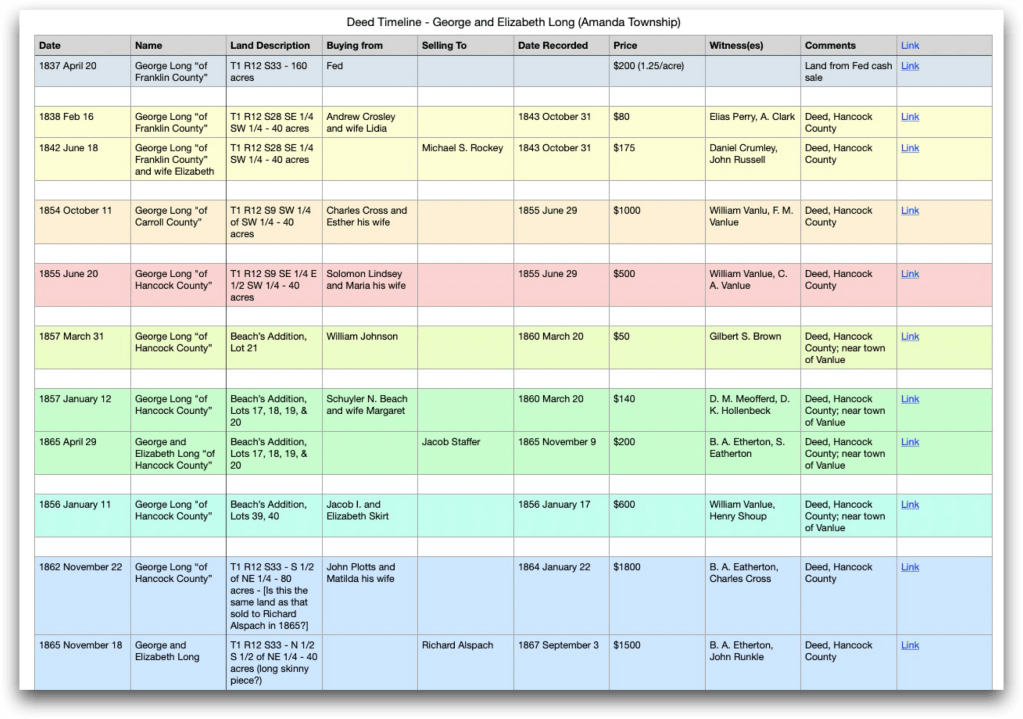

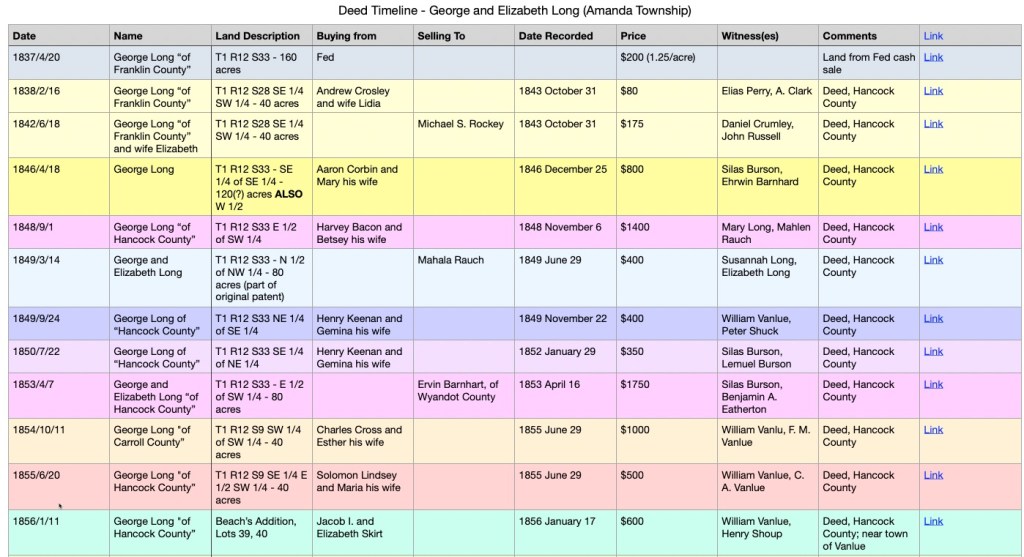

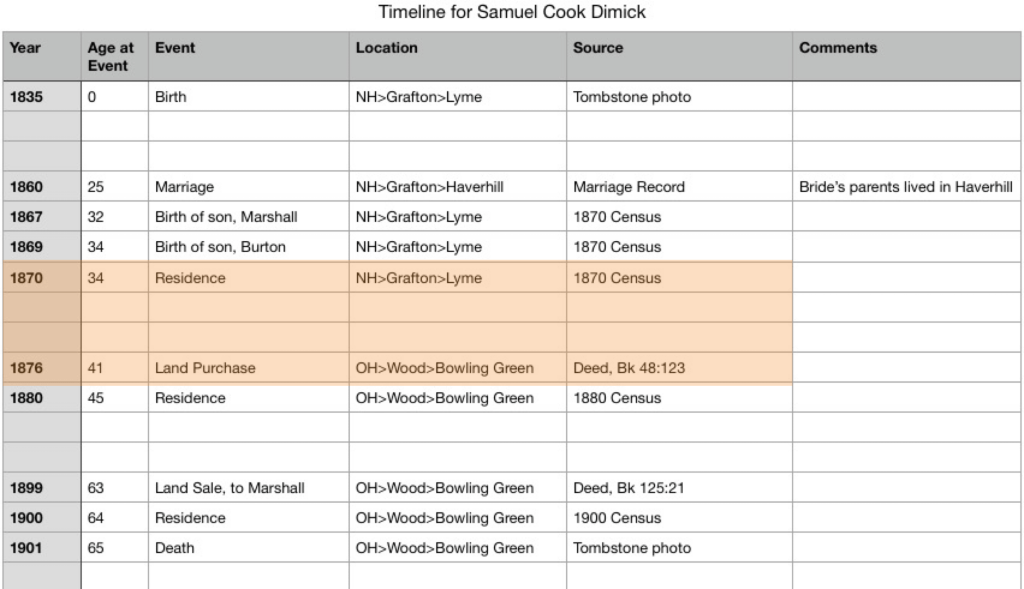

Here is an early version of the timeline. The orange box shows the gap in time between when he lived in New Hampshire and when he moved to Ohio. This is where I started asking some of those questions I mentioned in a previous blog post.

What records could I use to fill in the gaps? To keep a long research story short, I looked at a lot of records, including city directories for Bowling Green, Ohio. They do not have them for these specific years, so I was out of luck in that regard.

I reread the county history.

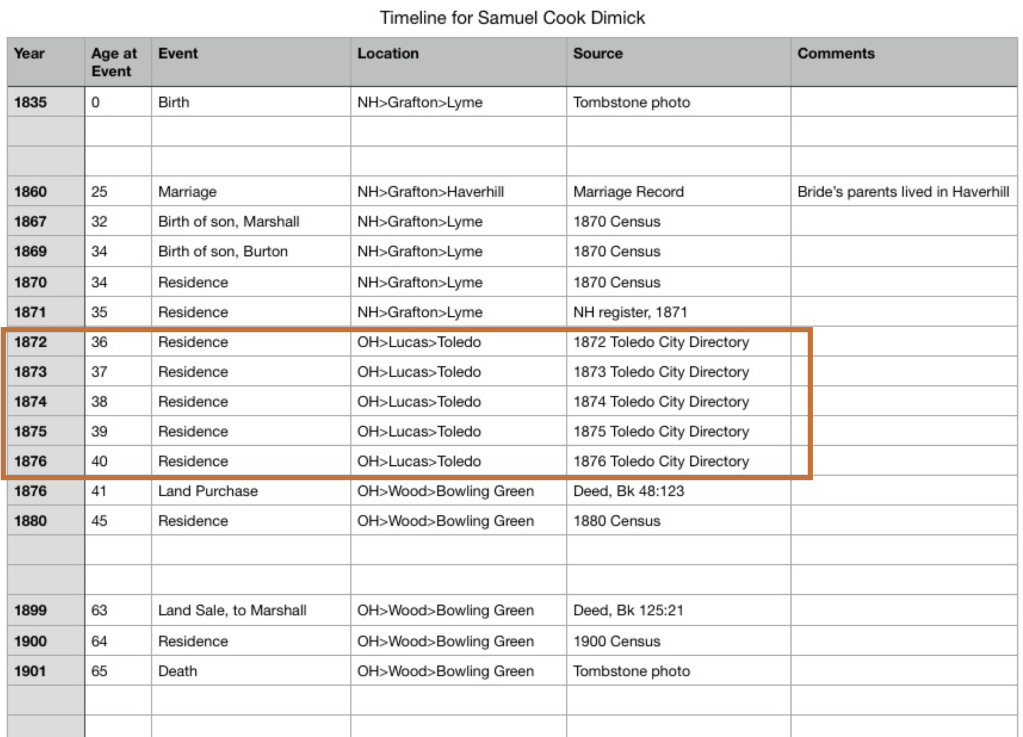

I’m sure none of you have ever glossed over things you read, have you? This is why it is important to go back and reread things you’ve read before. I had learned a lot since the first time going through the county history. But the answer I needed was right there in front of my face. The family lived in Toledo for a while before he moved the family to the “Old Williams Farm” in Wood County. This allowed me to go back to city directories, but this time to directories for Toledo, which is in Lucas county. Sure enough, I found Samuel live there for the roughly five-year gap.

This allowed me to fill in the gap and ultimately answered the question about why the moved from New Hampshire to Ohio. The city directory shows that Samuel worked for “H. M. Clark & Co. Manufacturers of Tin and Japanned Ware.” In the 1870 census, Samuel’s occupation was in “tin.” Turns out, H. M. Clark is roughly the same age as Samuel, also born in Lyme, New Hampshire, and they served on a town council together in Lyme. So, Samuel moved to Ohio for a job opportunity.

Other research has filled in Samuel’s timeline beyond this, but the visualization of your known information allows you to get more detailed and fill in those gaps, thus building a more robust understanding of your ancestors.