I’ve been working through my prior research on my Avery family from Wood County, Ohio. I’ve been going through my old research and mostly filling in blanks with the now low-hanging fruit of “easy” records hinted to me from Ancestry. Things such as census records, vital records, obituaries, and so on. I found another example of “trusting” old research in my binders.

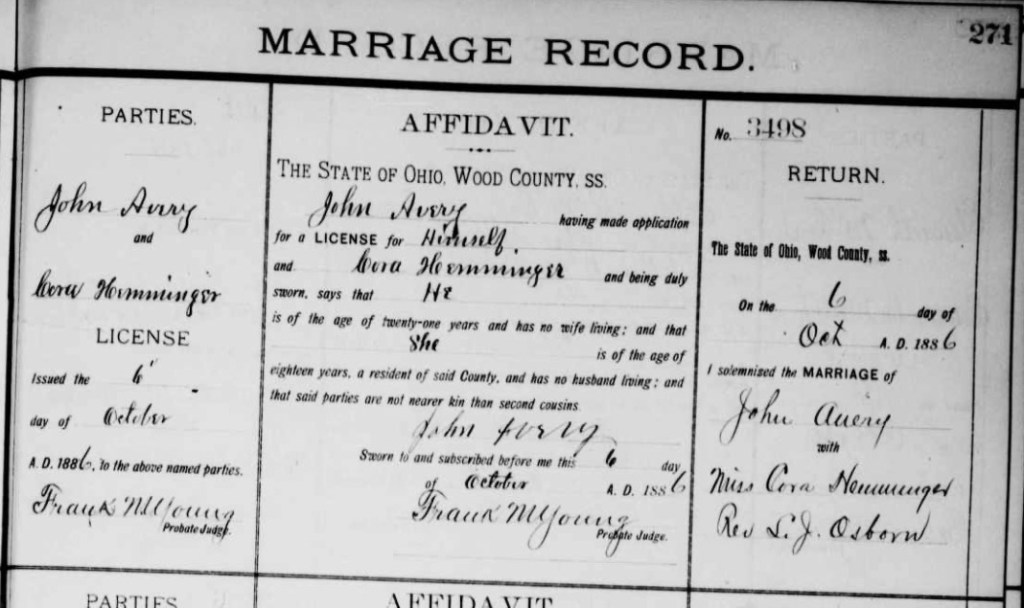

I’m working through the children of Gilbert Z. Avery, just grabbing their basics: birth, death, census, marriage, and obits, generally. According to my previous “research,” Gilbert’s son John B. Avery was married to Cora May Hemminger. I have their marriage record. They married in Wood County on 6 October 1886.1 However, as I’m working through the records this time, starting with Gilbert’s obituary and working through finding his children in the census records as adults, I found John B. Avery, in Arkansas where his father’s obituary said he would be. His wife was not Cora; it was Josephine.

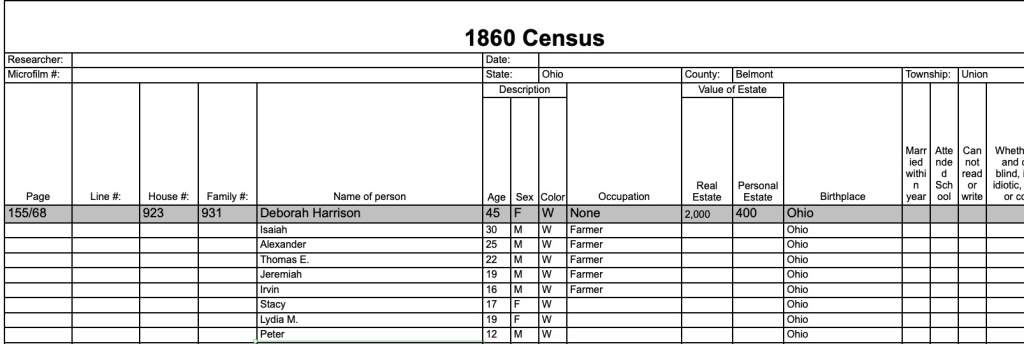

Not to worry. He may have married twice. When did Cora die? Hmmm, not until 1939. John is in the census with his wife Josephine for most of his adult life. He and Josephine married in about 1878, a full ten years earlier than the marriage record for John and Cora. John and Josephine are together in the census from 1880-1930. John died in 1932 in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. So, John could not have been married to Cora. I set out to figure out where I went wrong.

It was another case of believing research done before me. This time from a genealogist cousin who had done a lot of the Avery research and who was kind enough to share it with me to get me started. I was looking back over her original family group sheet she shared, and there it says that John B. Avery was married to Cora Hemminger. There is a note that he “resided in Pine Bluff, Arkansas?” So, she wasn’t sure about that, but there is no mention of Josephine.

I found the marriage record back in my early days and didn’t question it. And I didn’t go looking for him in the census. I DID put him in one of my early public trees. I did some searching in online trees for him, and I’m happy to say that most trees did not make the same mistake I did. Phew. Most of them have Josephine or no wife at all. Thank goodness.

I also did some searching on Cora Hemminger. I wanted to make sure she was a real person and who she was married to if not John B. Avery. In my Ancestry tree, she has a lot of hints. And she is married to John Avery, of course. But she’s married to John Orlando Avery. They also lived in Bowling Green, Ohio. John Orlando Avery’s parents are Joshua Orlando Avery and Harriet J. Manley, of Groton, Connecticut. My Averys were from New York state. So, I’m not sure they are related.

Let’s be fair. The internet, digitized images, and revolutionary tools like full-text did not exist when my cousins began their research. This has definitely made it easy for me to figure out the mistake in a matter of minutes. This is all at my fingertips now, whereas it wasn’t “back in the day.” The moral of the story? It’s a good idea to check your old research and reevaluate some of the early work you trusted.

1. The marriage record is at FamilySearch: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939K-BP64-D