When you are starting to work on a more difficult research problem, beyond the collection phase, you’ll want to make more directed, pointed, plans for your research. Here are the steps I take to plan research:

- Think about your research question. Clear it up if it isn’t already clear. Who exactly are you trying to identify? Have you singled out a unique person in time and place? Don’t make it too complicated or to simple. There is a Goldilocks effect when it comes to a research question, one that is “just right.”

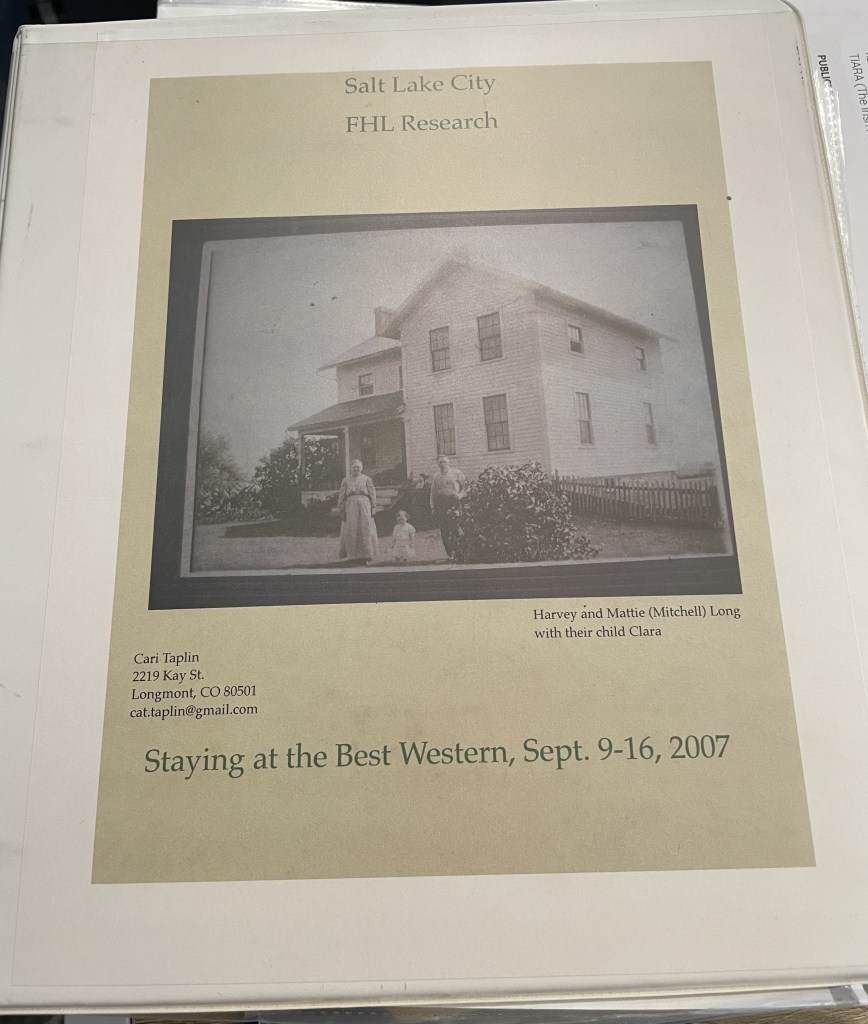

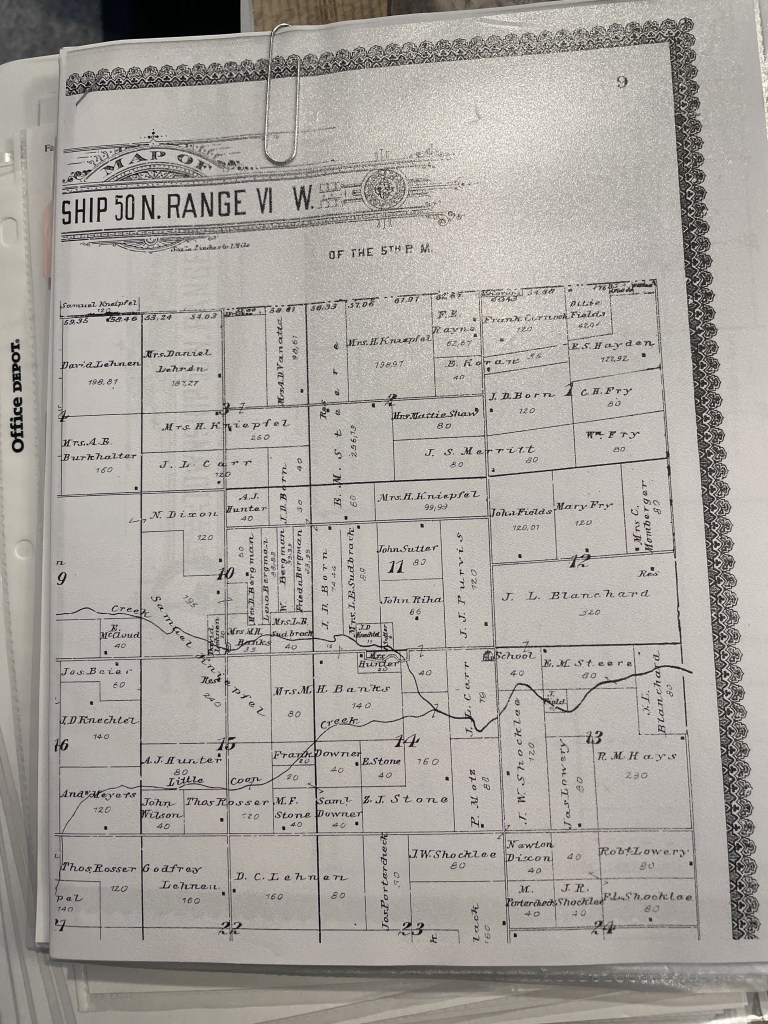

- I catalog my starting point information. During this process, I reevaluate what I have. Many times this is research I haven’t looked at for a long time. Are the assumptions I’ve made sound and based on documents? Is my starting point information actually correct and known to be for the right individual? Are there any conflicts in the starting information? I write all of this down, usually in bullet points. If there are a lot of conflicts, they may get their own section. Sometimes (often?) I find some kind of mistake I made in my reasoning, often because I didn’t know then what I know now. I have more experience and knowledge now and sometimes that breaks through a brick wall all by itself.

- I make a list of what I need to do to resolve anything from step 2. If there are conflicts, can I give sound reasoning as to why they may exist? If not, what additional research do I need to do to resolve them? If I made an incorrect assumption, what do I need to do to correct it?

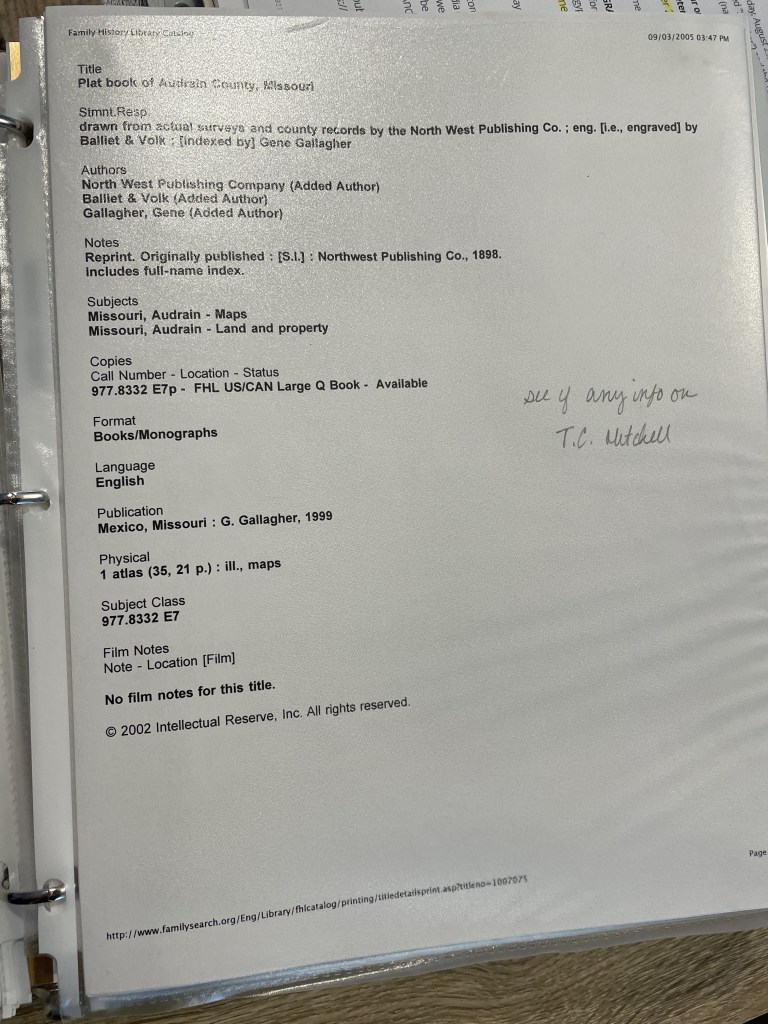

You’ll notice that everything above is not even planning the RESEARCH yet! - I survey the records that are available (both online and off) that may answer my research question. I utilize the catalogs available on websites such as Ancestry, FamilySearch, and local public libraries, archives, universities, and etc. as it applies to the topic or the location I’m working in. From that research, I may make a larger list, but I truly start with a top 3-5 items. Invariably, you’re going to find something that changes the course of your research. Spending too much time creating an extensive and detailed plan will likely be a waste of time.

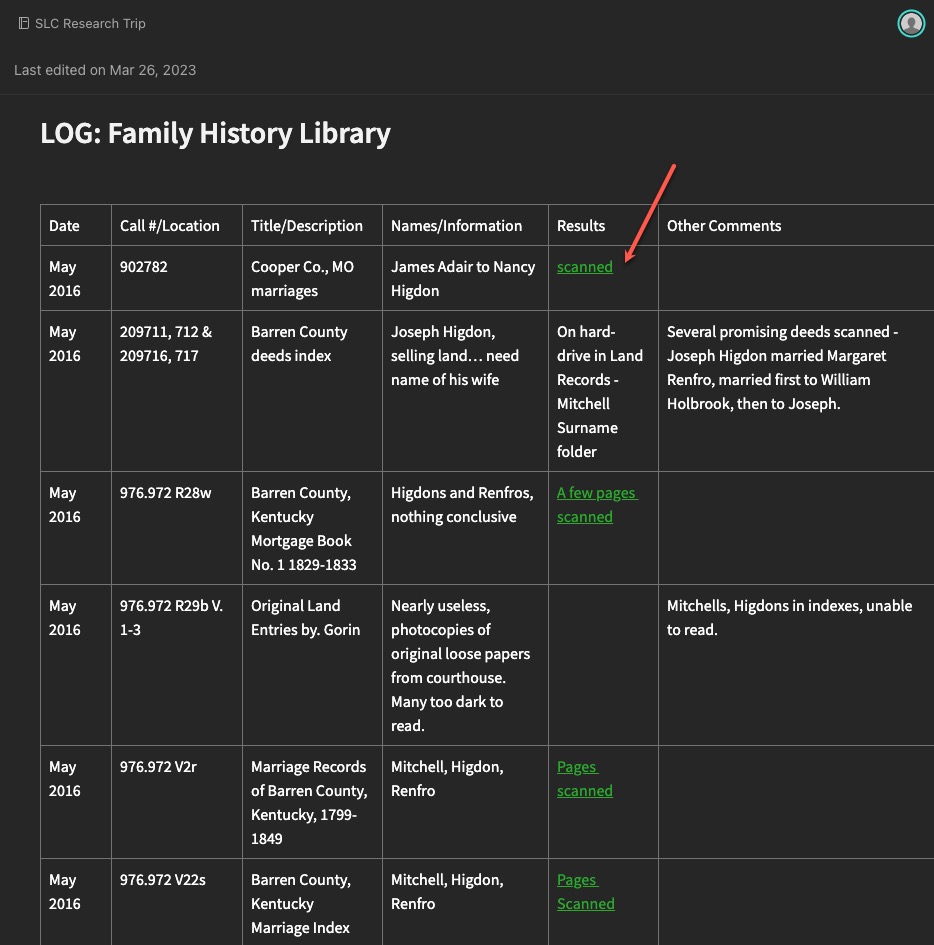

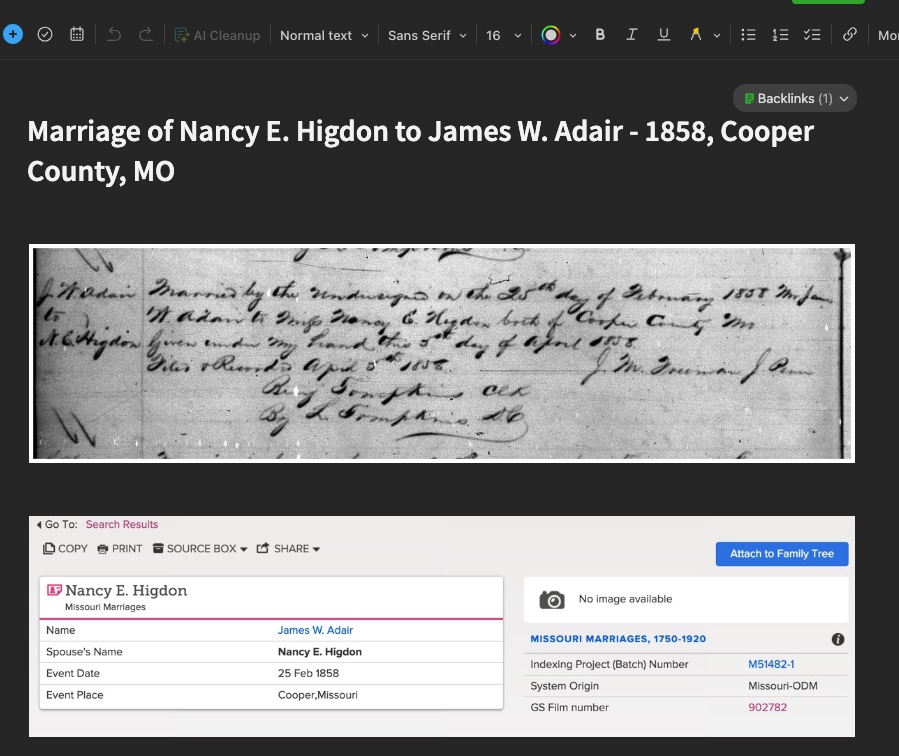

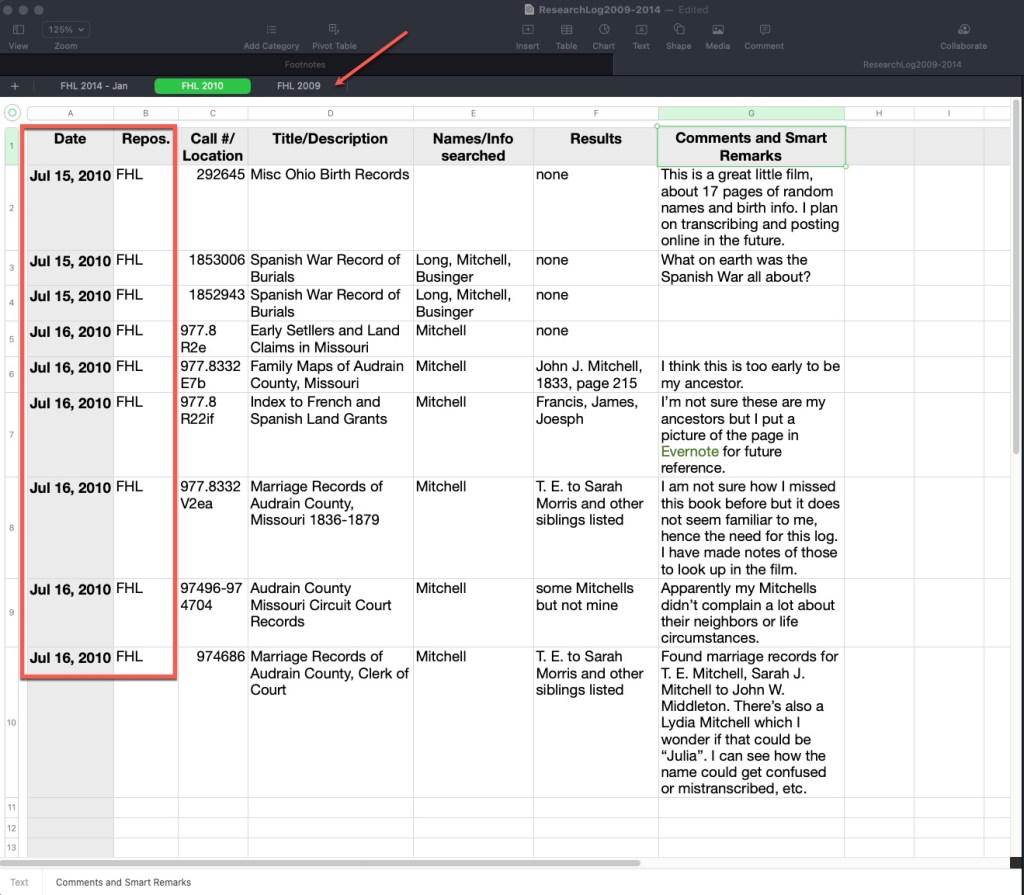

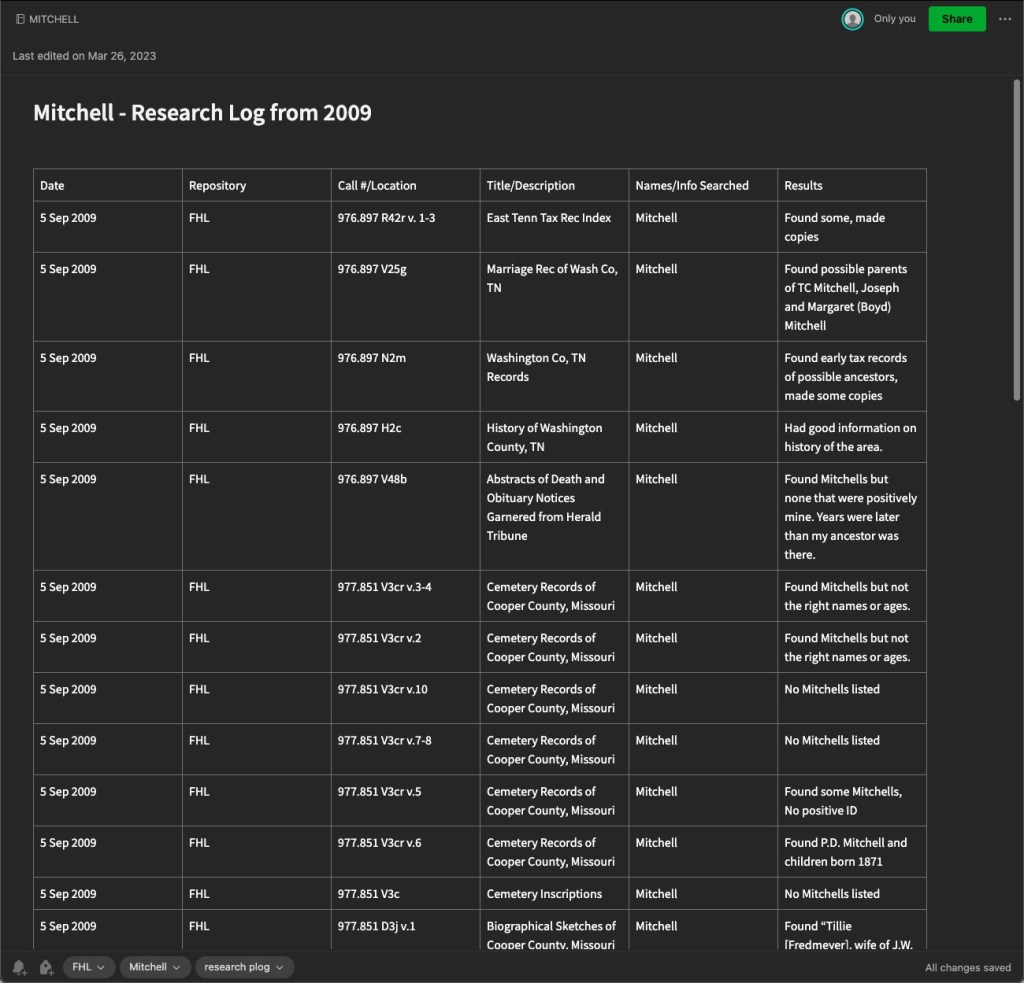

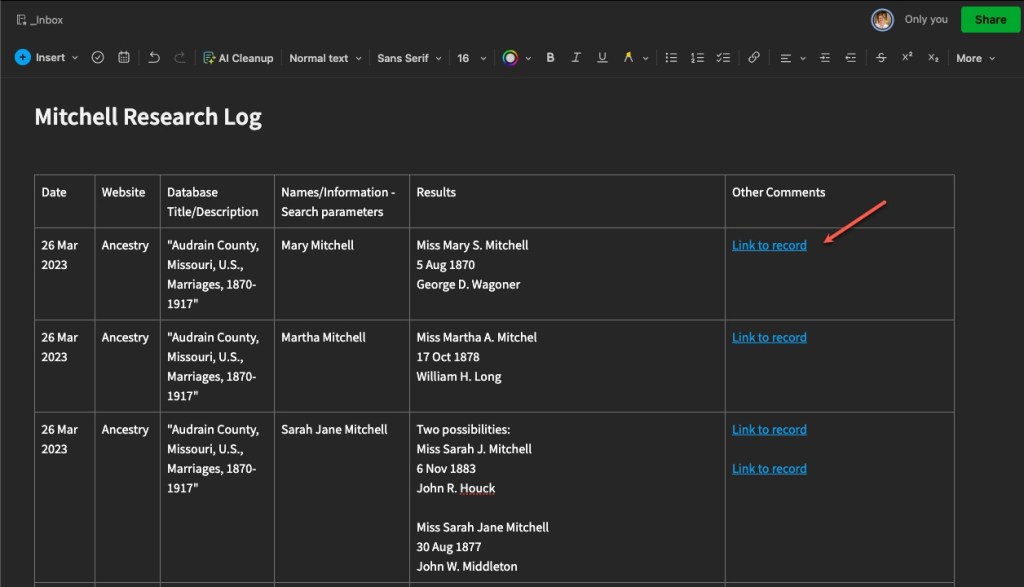

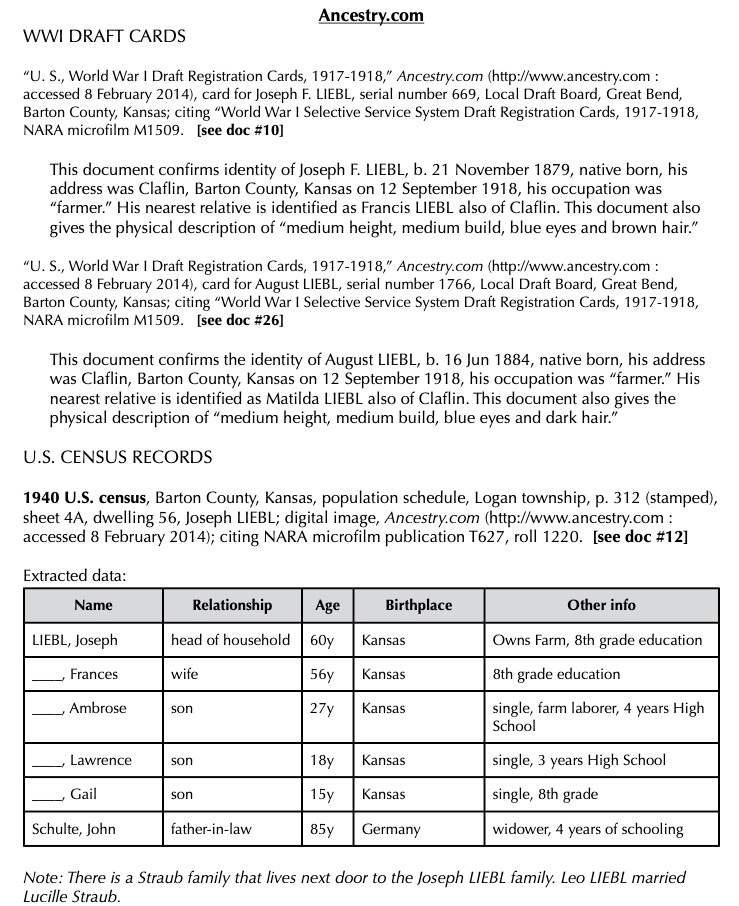

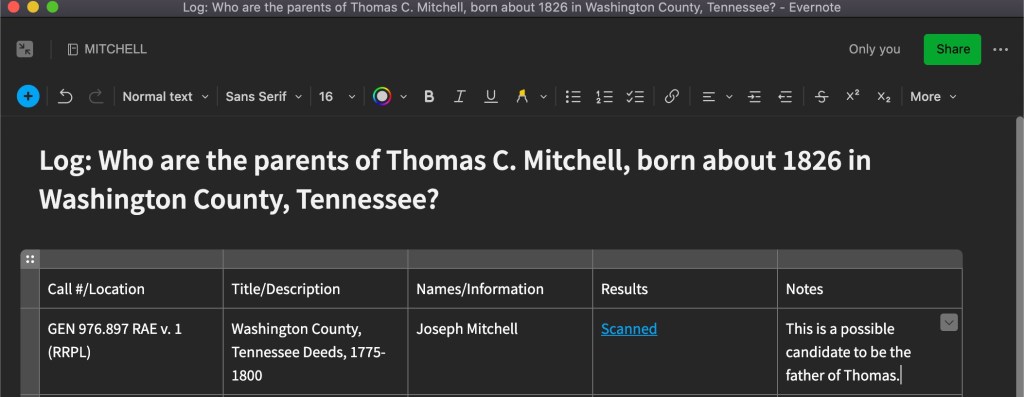

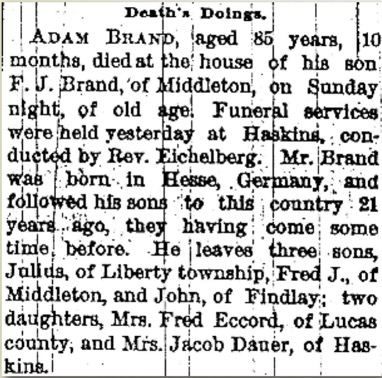

- Conduct the research! This is the fun part. Look at what you planned on looking at. Note why you are looking at it (purpose of search) and what you found. Collect any URLs, waypoints, download images, note any conflicts, note any negative findings, and note any changes in your plan or direction of your research.

Whether you are in collection mode or brick-wall mode, planning your research is an important part of being efficient with your research time. Hopefully you found some trips or tricks you can use from this series on how I do it. Everyone thinks and plans and organizes differently. So take what you think will work for you and go make it happen!

Happy plogging!