Now that we’ve talked basics and you’ve made some decisions in terms of how to put your locality guide together, let’s go over some resources you can use to build your guide. These are places you can turn to for general to specific information that can build your guide’s usefulness.

First, let’s examine some resources for general information.

- FamilySearch Wiki – Use this fantastic wiki for general information about a genealogical topic (such as probate records, vital records, census records, etc.) or about a location (county, state, or country).

- Cyndi’s List – Use this valuable resource to find general websites of interest that can help you build the historical and geographical portions of your guide.

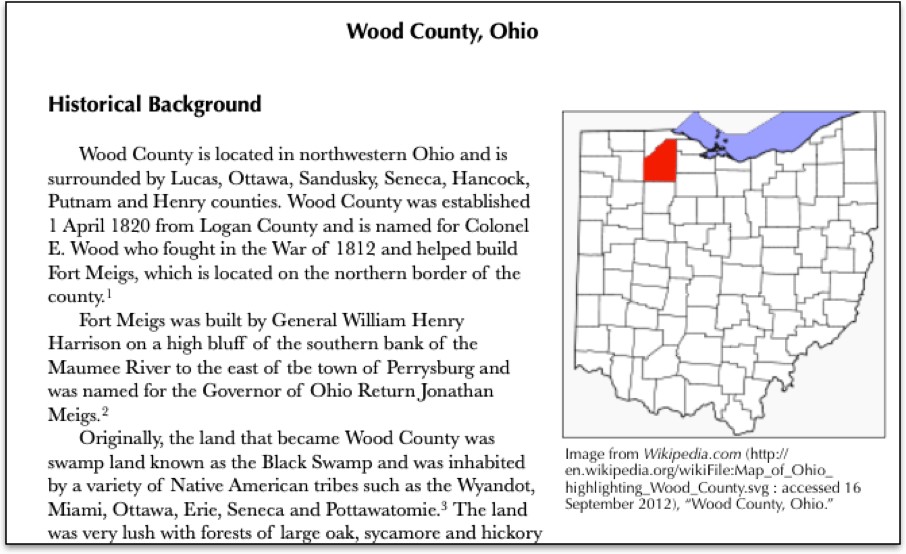

- Wikipedia – Use this for general historical information about a particular location or topic, I find Wikipedia most helpful for a quick overview of a subject and then determine what I want to know more about, then will look for more specific sources of information. Often, Wikipedia articles have very helpful citations that can lead to other sources of information on a topic.

Next, let’s examine some resources for specific information.

- FamilySearch Catalog – Use this part of the FamilySearch site to find books, microfilms, digital collections, and databases for specific localities. This is where I go to identify many of the collections that are available for a particular county.

- Cyndi’s List – Also useful for links to websites about specific subjects or locations. I often find websites here that I didn’t even know I needed!

- Local public libraries – Look for the public libraries that serve the county (or town or region) you are building your guide for, especially one that has a local history collection. Examine their catalog and websites for useful resources.

- Local college or university collections – Many colleges and universities have archives and manuscript collections that can have useful collections or online resources useful to note in your guide.

- Local genealogical and historical societies – Look for the nearest genealogical society that may cover your guides’ area. Check their websites for any databases, publications, collections, or services they may provide.

- Local museums – Many locations have historical or specialized museums that may also have a research room. Check for those in your area of focus.

- Books and journals – Look for histories, reference books, journals, articles, and other published materials that cover your guide’s area of focus. You may find them on WorldCat, Amazon, at the local public libraries, in bibliographies, and so on. These may be quite useful to note in your guide and provide you with content for certain portions of your guide.

Now that I’ve shared some of the resources I use to build my locality guides, I will share next time more about the specifics of what to include in your guide. We will go over each of the sections, how I put them together, what I like to include, and other tips.