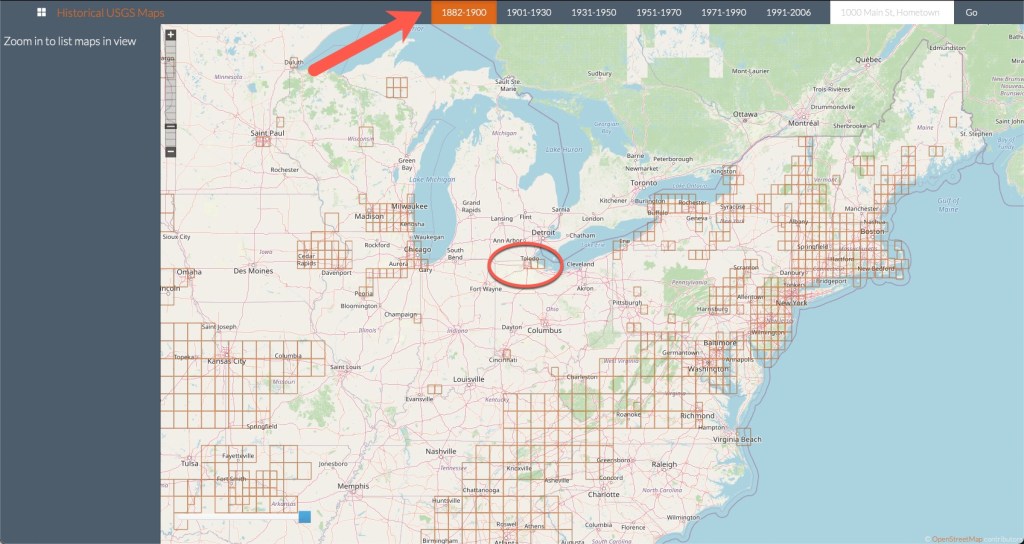

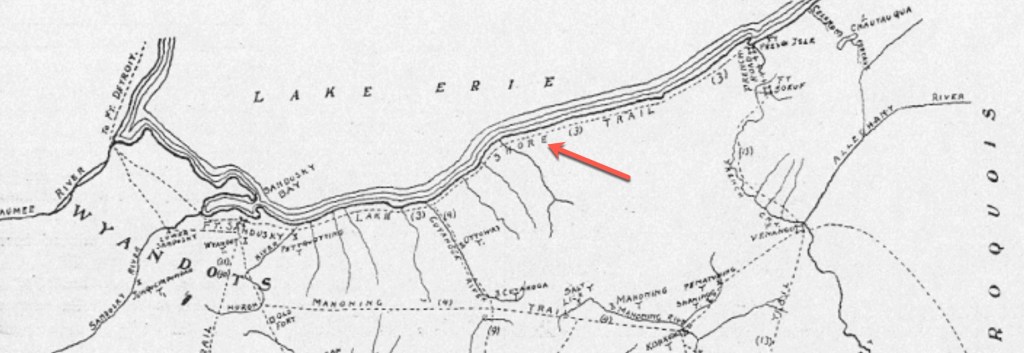

When my ancestors moved from Lyme, New Hampshire to Toledo, Ohio, what route might they have taken to get there? Given the time period, there might be several ways our ancestors could have gotten from point A to point B. Lyme is northeast of New York and the Erie Canal. When they moved to Ohio, the Erie canal was up and running. They could have taken a train or a wagon south from Lyme, then used the Erie Canal to travel to Buffalo, New York. From there, a steamship on the Great Lakes to Toledo is a viable route. This is the one that I like to think they probably took. However, without a diary, letters, or ticket stubs, I’ll never know. But we can make some inferences by looking at map and researching the routes.

There are a lot of different types of transportation that could come into play when assessing the options for your ancestors’ migration:

- Indian Trails

- Wagon Routes

- Train Lines

- Canals

- Steamships

- Roads and Interstates

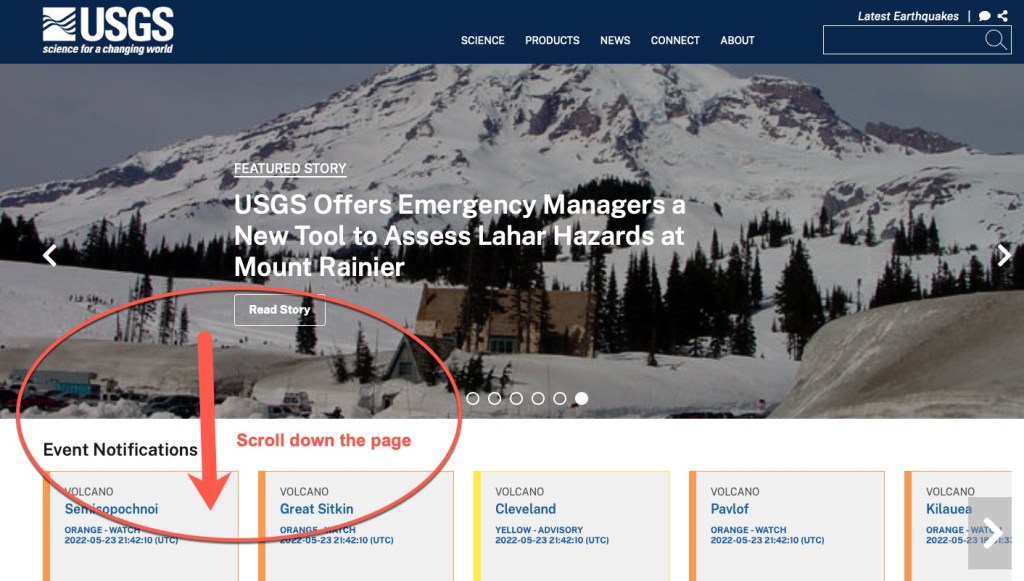

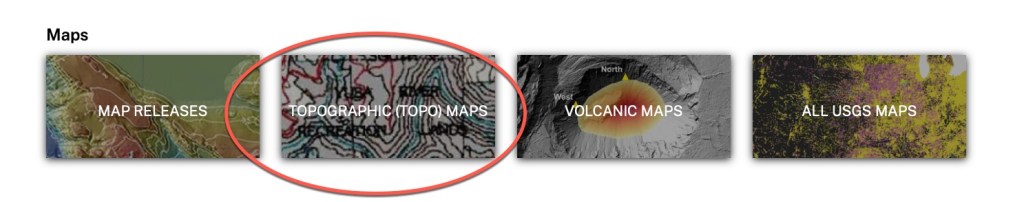

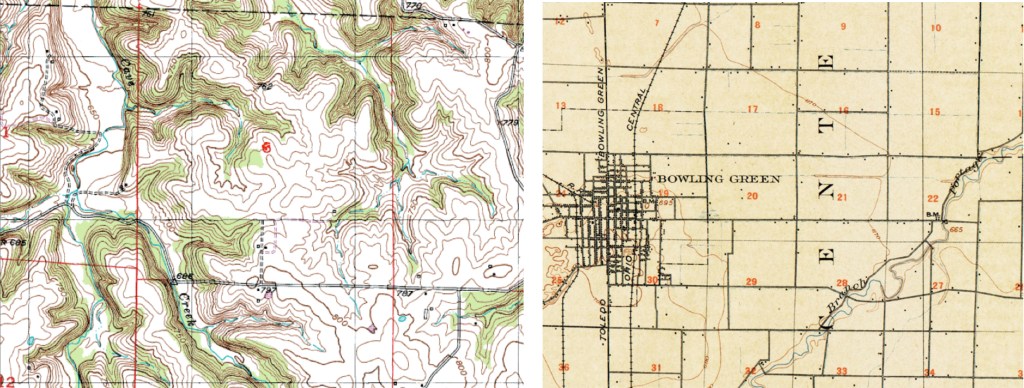

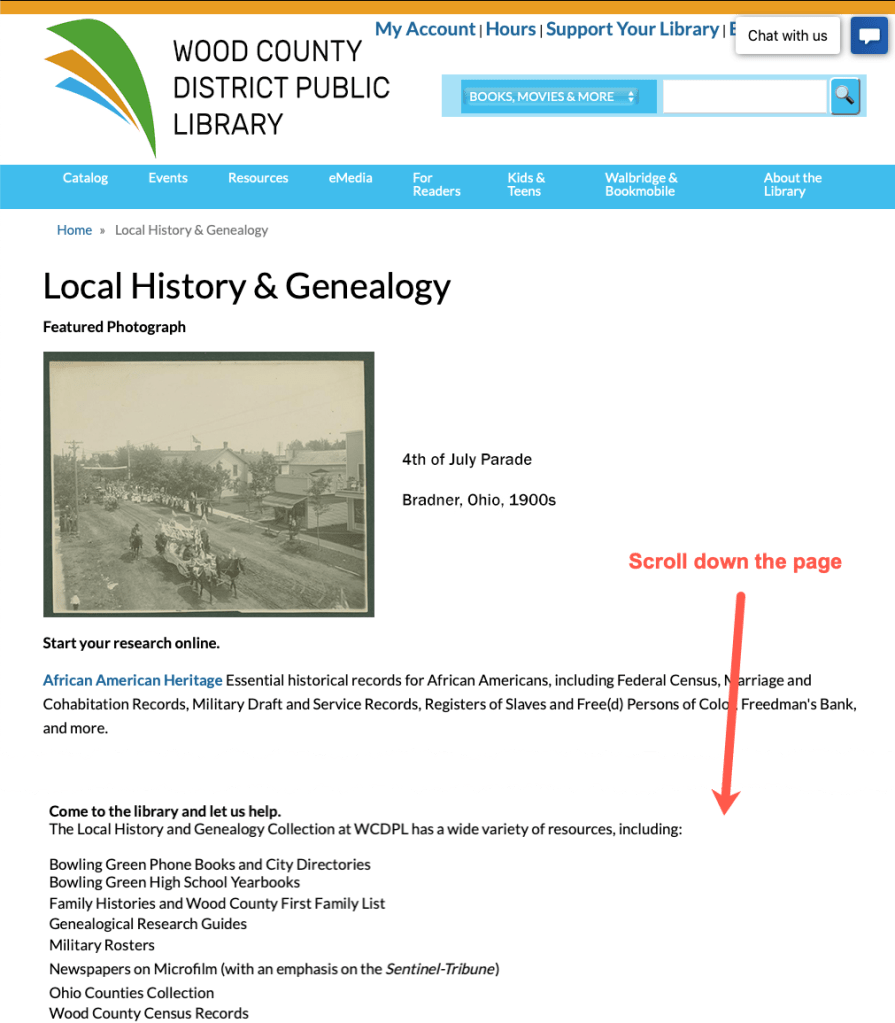

When I try to decide how my ancestors may have moved across the country, I first try to find a map as close to the time of their movement as possible. I’ll try to find a couple of maps that show various different types of transportation.

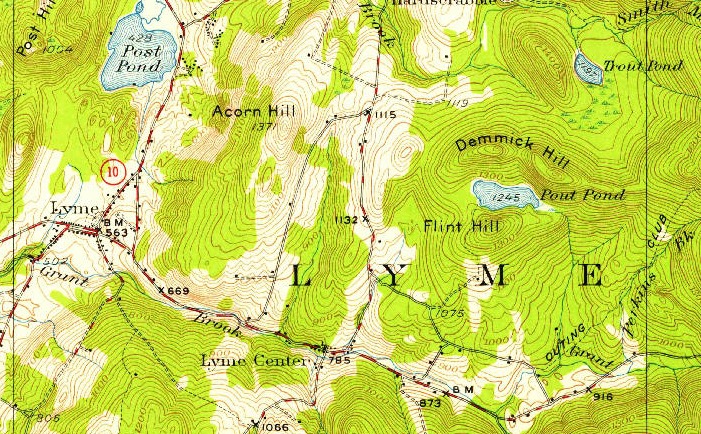

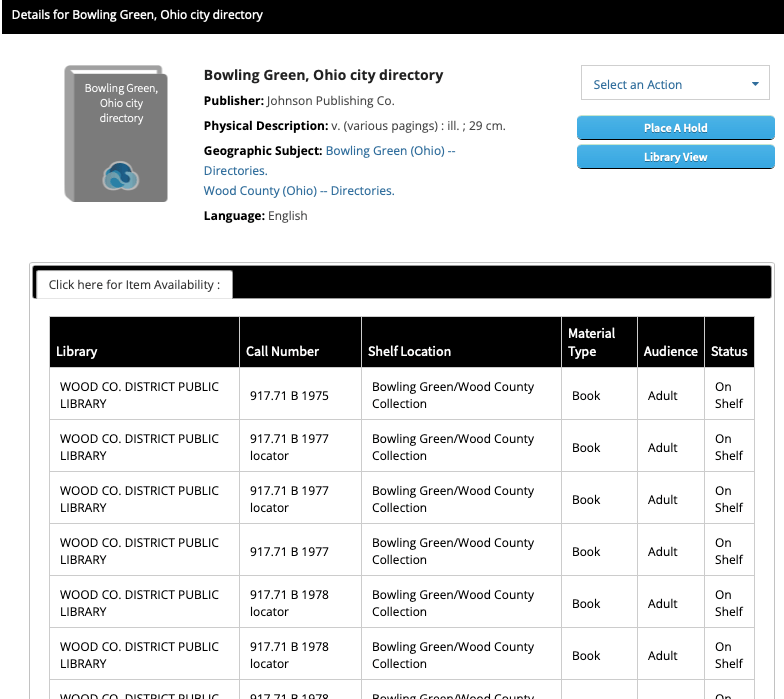

For example, Samuel Cook Dimick moved his family from Lyme, New Hampshire, I set out to determine how they may have moved.

Lyme, New Hampshire is approximately where the blue star is. They then would have made their way to Albany, taken the canal to Buffalo, then a steamship on Lake Erie to Toledo. How might they have gotten to Albany?

This map is from 1894, it is not perfect, but it is near the time that they moved to Ohio. There appears to be a rail line that follows the Connecticut River south. They could have boarded near Lyme at a depot. Lyme is on the river. (Here is a link to the map at the Library of Congress so you can zoom in and scroll around.) Then you would just look for a similar map for Vermont, and Massachusetts and New York, until you’ve examined all of the possible rail lines.

What about when they made it to Lake Erie?

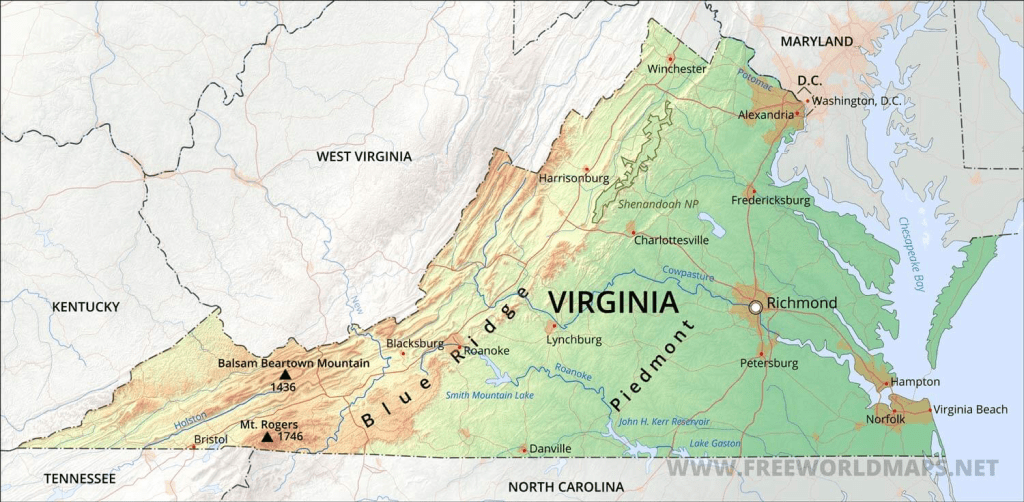

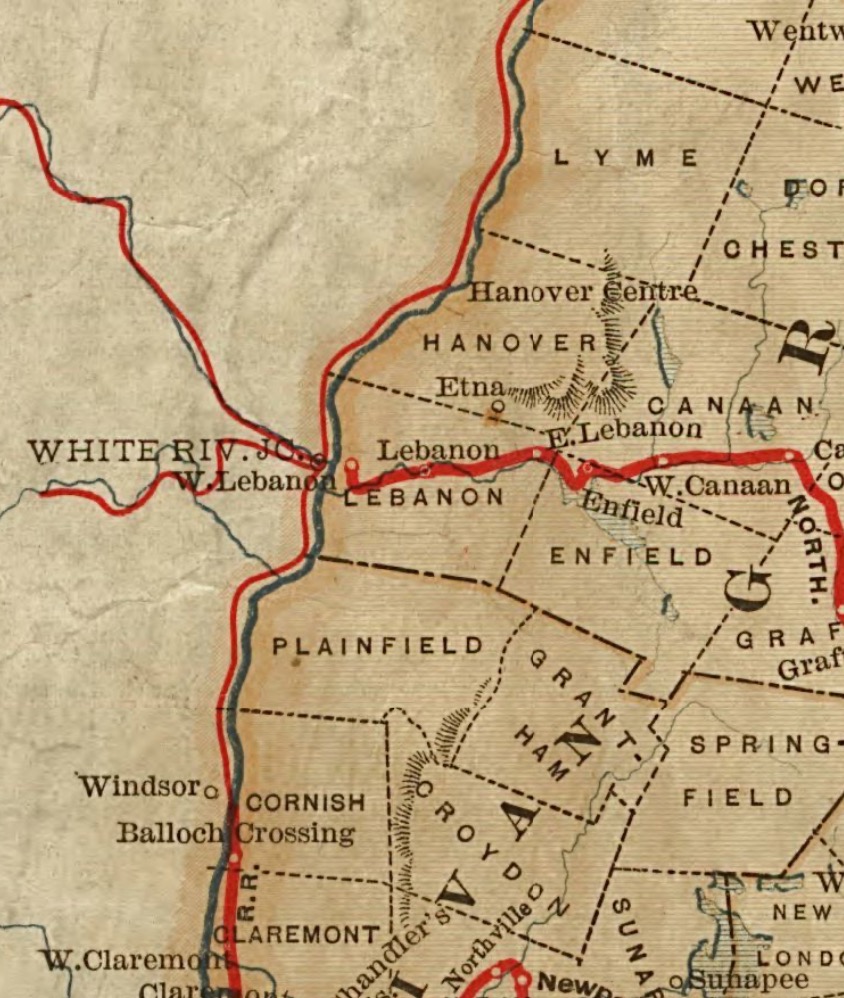

They moved to Toledo, Ohio; travel via the Erie Canal and Lake Erie seems most reasonable. But there were other options. What about wagon roads? Wagon roads were built on top of old Indian trails. Eventually they became well-known highways and interstates.

It is a fun imagination exercise to try to determine the possibilities. Maps are a great way to do this kind of exercise.

Next time, we will look at one of my favorite kind of maps: the bird’s eye view!