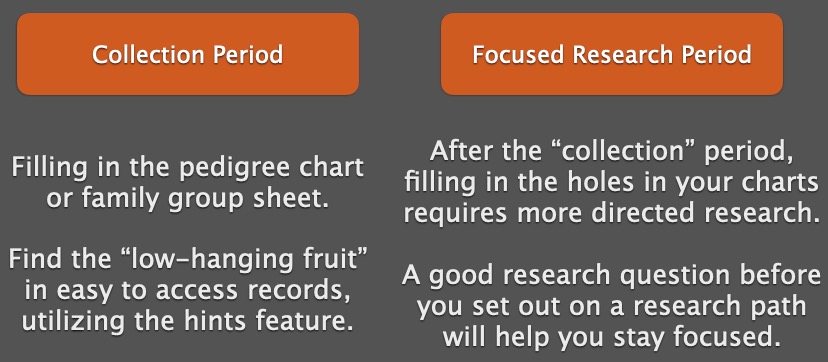

Several posts ago, I talked about how I “believed” others who had built the family tree before I started researching. I put a lot of “trust” out there.

“I believed everyone out there doing genealogy on the same families as me had been doing it longer and therefore must know more than I did, must have found the records already, and therefore their pedigrees, family group sheets, and trees posted online were correct.”

Well, I have just discovered an error that I’ve believed, and other genealogists before me had believed as well.

During my tree cleanup, I have recently been working on the Avery family. In one generation, the Averys and the Meekers lived next door to each other. From that, four Avery siblings married four Meeker siblings, creating a lot of chaos in my family tree. One generation down from this, I had another Avery marrying another Meeker. I hadn’t noticed before, because the Averys and Meekers are so intermingled. However, today, I noticed that this coupling was not in the right generation. I have in my tree, as many others do, that Mahlon I. Meeker married Pauline Avery. This would make these two first cousins. As I set out to research that, I could not find a marriage record for them, at a time when the marriage records exist and are pretty good.

So, I did a more global search for the Avery bride. I noticed a hint to another online tree that had the right groom, but the bride was Pauline Dunning, not Avery. At first, I thought this tree must be incorrect. So many trees have Pauline Avery as the wife of Mahlon I. Meeker. Well, I’ve learned that genealogy is not democracy, and just because there are so many “votes” for one thing does not make it true.

I reviewed the information I had that gave Pauline’s husband as Mahlon I. Meeker: they were all things from other researchers, not actual records. (See, I was believing them.) Then I reviewed the actual records I have. Pauline’s father’s obituary lists only “Polly deceased.” It does not give her a married name like her other siblings. Following the records for Mahlon I. Meeker, I do find a marriage record for him to Paulina Dunning. He is the correct Mahlon I. Meeker, but she was not the correct Paulina. I did consider that maybe Paulina was previously married before marrying Meeker, but I did not find that to be true. Mahlon’s wife’s maiden name was in fact Dunning and her parents have been identified; they are not Averys.

This was just the perfect situation to demonstrate why it is important to go back through your old research and clean it up. The good news, at least in this situation, is that both Mahlon and Paulina Avery are still in my tree, so I’m not lopping off an entire branch in this case.

Now on the hunt to find out what happened to the “real” Paulina.